We are the Third Video.

Intensely personal, sobering, and candid, uncover the ingenious visual metaphor hidden within this work's simple appearance.

I first started studying art in Junior College. Fine art, to be more precise—the kind found in white-walled galleries, sold for millions, and splashed with tomato soup. In those two years of studying 48 artists and over 144 works, Bill Viola’s Heaven and Earth (1992) remains my favourite.

What can you find?

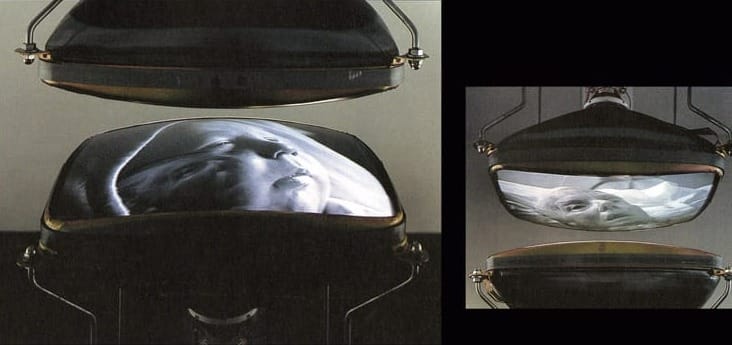

Visitors encounter the installation in a dimmed room. Two wooden columns protrude from the floor and ceiling respectively, each with a video monitor attached to its end. The monitors are positioned facing each other, separated by a gap of approximately 5 centimetres.

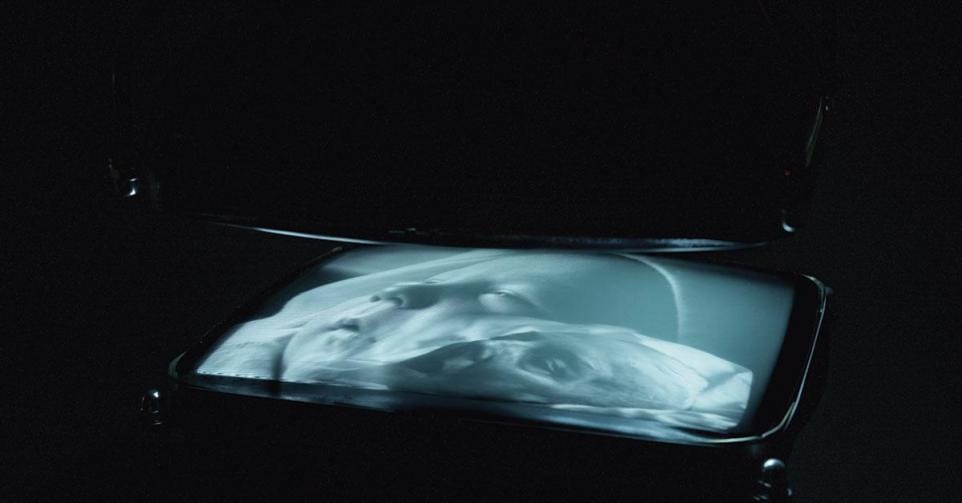

Each screen plays a black-and-white video. In the upper screen, facing the floor, Viola’s mother lies on her deathbed in her final hours. In the lower screen, facing the ceiling, Viola’s newborn son scrunches his face as if to cry. Both videos loop silently, tinged blue in the dim light.

What could this mean?

The visual metaphor here is apparent. One can easily assume the video above represents death, or 'Heaven', while the one below represents the generation of new life, on 'Earth'. The physical space between the two screens extends into the rest of the room, in which you stand and exist as the viewer—we are the third video, acted out in real time.

In taking notice of how one is made to experience the work, one can directly uncover further nuances in the work’s meaning. For example, the only way to view each video with clarity is to align oneself alongside the one opposite it. On the other hand, if one were to squat just enough such that both screens appear parallel to each other (hence assuming the stage between birth and death), one would find themselves existing in the physical space between 'Heaven' and 'Earth'. In this case, the contents of neither video are easily discernible, pointing towards mankind’s inability to understand the mysteries of birth and death.

One of my favourite things about this piece is how the 2 images appear to be complete opposites of each other, yet still feel irrevocably connected. Despite the obvious contrast between the skeletal visage of Viola’s elderly mother and the swollen, cherubic face of his newborn son, an unmistakable sense of relatedness remains. This is perhaps due to the knowledge that the two individuals are directly related, but may also be a result of their similar facial expressions—both appear tense and wrinkled up, as if in pain or discomfort.

Viola himself contributes to this feeling of connectedness in an ingenious way: the glass surfaces of each screen and their close proximity allow for the two opposing videos to reflect onto each other. Consequently, each image of birth and death appears superimposed, and viewers are physically unable to view each video independently. Heaven and Earth are eternally haunted by a spectral projection of the other, as are life and death.

What makes this work so special?

Through the incorporation of raw, uncensored home videos of his loved ones, Viola constructs a visual metaphor that is both intensely personal and sobering. However, another interesting perspective to consider is that of viewers who are unaware of the work’s personal context—one would plainly see a dying woman and a young infant, owing to the videos’ straightforward depiction. This candid vulnerability with which the two events are portrayed not only makes this work especially impactful, but also openly lays out the reality of mortality before our eyes. With this uncensored portrayal comes a sense of acceptance for what life and death are.

What can we learn from this?

In silence, the videos loop continuously, illuminating the room with a flickering, almost ghostly glow. The space in-between the monitors connects to the larger space within the gallery, which then connects to all the space of the world outside of it. Even when we leave the room, we will remain in this in-between space until our last breaths.

With a physical metaphor like this, Viola reminds us that we cannot discuss life without also being reminded of its inevitable end. In the same way, we cannot discuss death without considering the life that came before it—and the life that will continue to come after it.

Bill Viola is a 72-year-old American contemporary video artist. His works most often rely on modern image and sound technology—picture larger-than-life digital screens (The Crossing, 1996) and videos slowed down to the point of feeling stop-motion (The Greeting, 1995). Viola’s pieces often discuss fundamental human experiences like life, death, suffering and consciousness. You may find out more about his work here.