Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia

At the end of it all, Living Pictures tells a story of subjectivity. Photography simply captures what one sees, and everyone sees differently.

Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia is the first major show on Southeast Asian photography to be exhibited at the National Gallery of Singapore. This fact may be surprising—many would assume that an institution as major as the National Gallery would take a natural lean towards showing local and regional pieces before even contemplating those from overseas. (Ironically, the fact that this show is the very first of its kind might just re-emphasise how little most Singaporeans know about Southeast Asian photography, especially from a chronological standpoint.)

I must admit that I, too, am guilty of this myself. Hopefully that has changed at least a little after visiting Living Pictures, but I am also aware that no single exhibition will be able to encapsulate so many decades of rich artistic history. While Living Pictures naturally remains condemned to this same fate, I nonetheless believe it succeeded spectacularly in being an easily digestible yet thought-provoking entry point to Southeast Asian photography.

The exhibition was housed in the Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery (and continues to be until August this year). It was, like most of the National Gallery’s exhibitions, pervaded by an elegant yet solemn atmosphere. No doubt that the museum’s dimmed lighting and lacquered wood floors added to this, but so did the miniscule number of visitors present in the gallery. I was accompanied by no more than 6 other visitors at any given point in time, despite the fact that the exhibition stretched across the entire third floor of the gallery. (Unfortunate, but not an uncommon sight in our country.)

Photography is arguably a one-of-a-kind art form in terms of the tools and methods one uses. While not as mainstream as drawing, painting or even sculpture, the general consensus is nonetheless that it fits comfortably within the realm of artistic practice. This is partly owing to its capacity for manipulation—photography captures, but also reflects. The viewfinder can never be truly objective. The intent of the photographer remains eternally apparent in whatever subjects they deem worthy of photographing, as well as in how they photograph it.

However, most of us rarely consider photography with relation to its history. This may be due to its ubiquity amongst younger generations of today. Teenagers snap away on their mobile phones while older generations (though certainly not all) largely still fail to own the casual art of modern-day photography.

Because of this, it is even easier to associate olden-day photography with huge, bulky cameras necessitating extensive exposure times.

Living Pictures showed me otherwise. The range of works displayed was rather large—from propagandic colonial postcards to royal portraits, to ancestral tablets and digitally-edited photos of today, the exhibition strung photographic collections together via an overarching chronological theme.

We begin in the colonial era, when photography was largely accessible only to the wealthy or white and was often used as a means to capture the exoticism of faraway lands. In Émile Gsell’s 1866 cartes de visite—posed, small-format portraits featuring individuals of specific ethnicities—portraiture is used as a means to transform people into mere cultural stereotypes. These postcard-like photos were often bought by caucasians as souvenirs and touted the exotic appeal of colonised nations.

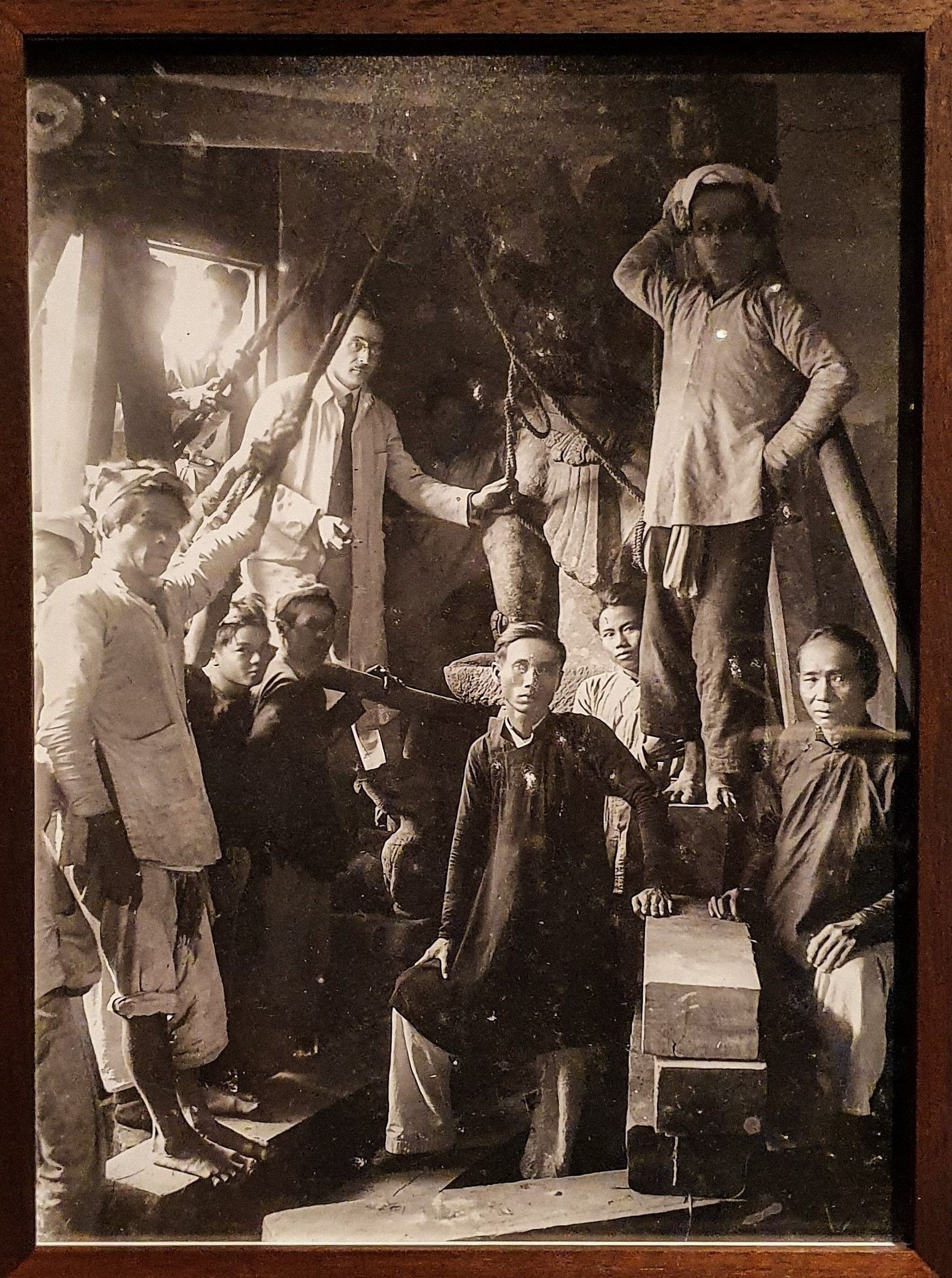

The rest of the exhibition brings us from the colonial era to the burgeoning days of Southeast Asia, all the way to contemporary society of today. We are able to witness the art of photography transmute through time, as it passes from the hands of our caucasian ex-colonisers into those of locals. We see it used in our ancestors’ free time; we see it in their homes and in their wars. We watch the element of creativity take root in the craft—from fabricating scenes using rudimentary props and backdrops, to modern-day digital manipulation and remixing.

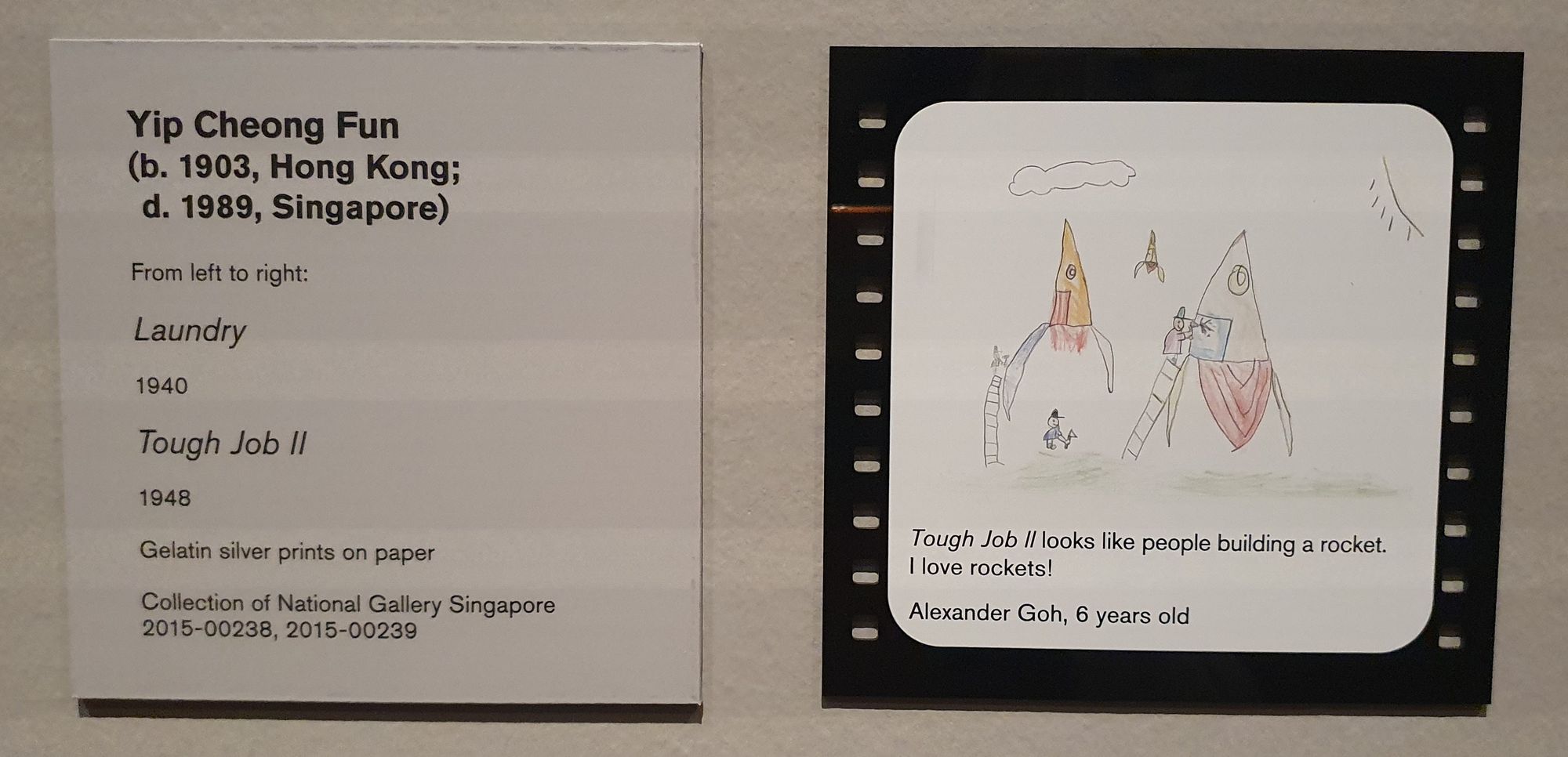

Conceptually, Living Pictures managed to be both intellectually stimulating and easy to understand. Its chronological format was a rather unique one to take, yet it remained easily digestible as adequate contextual information was provided in the accompanying artwork labels. The exhibition also experimented with other forms of meaning-making—in the first few galleries, for example, one could find audio readings of letters and diaries from individuals who had been involved in photographic processes back then (such as employees at photography studios). Occasionally, artwork labels were also accompanied by relevant musings submitted by members of the public: coloured, chicken-scratch drawings by young children. Poems by university students. Personal accounts by artwork conservators who had a hand in preparing the corresponding works for exhibition. All of these tidbits constructed a feeling of community—because of it, the viewing experience felt more like an active exchange rather than mere passive absorption.

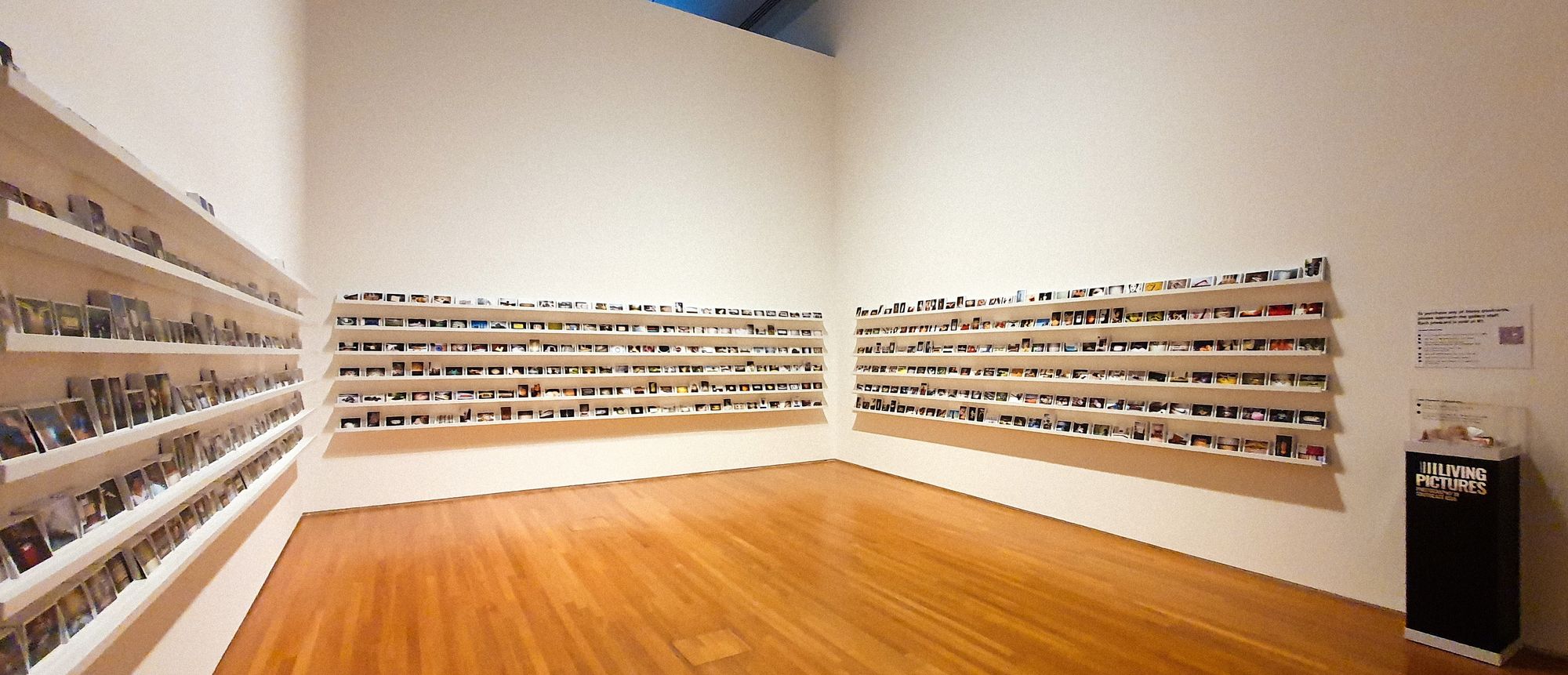

At the very end of the exhibition, visitors are also allowed to purchase postcards for a dollar each—the collection, named God Bless Diana, includes 550 unique photographs taken by Malaysian photographer Heman Chong. I perused the postcards for a while before realising they were arranged thematically, each row constituted by photographs that all contain a common subject. There were rows dedicated entirely to pictures of people sleeping on the streets. Others to vehicles of any kind, or street markings forming the shape of an X. I was rather amused to find that the most purchased postcard, evident from the depleted stack, was a photo of graffiti that told viewers to, ‘FUCK ALL THE AUTHORITIES’: yet another sign of the times, manifesting itself in our selective consumption of photographic media.

At the same time, there were unfortunately still some minor issues that interfered slightly with the seamless experience. Another lady visitor in the gallery was complaining (rather loudly) about a particular series of works adorning the wall closest to the front door—an archive contributed by G.R. Lambert & Co., one of the most successful photography studios in Singapore in the late 1800s. This collection stretched across much of the wall and consisted of a mosaic of framed black-and-white photographs, many of which were documentations of local landmarks the early days as well as posed portraits of Asian settlers. The problem, however, was the fact that all image names and details were compiled in a single label on the right side of the wall. As a result, visitors needed to walk back and forth in order to put name to photograph. While I held back from providing as much verbal feedback as the lady had, I, too, found myself too lazy to partake in the back-and-forth and moved on quickly.

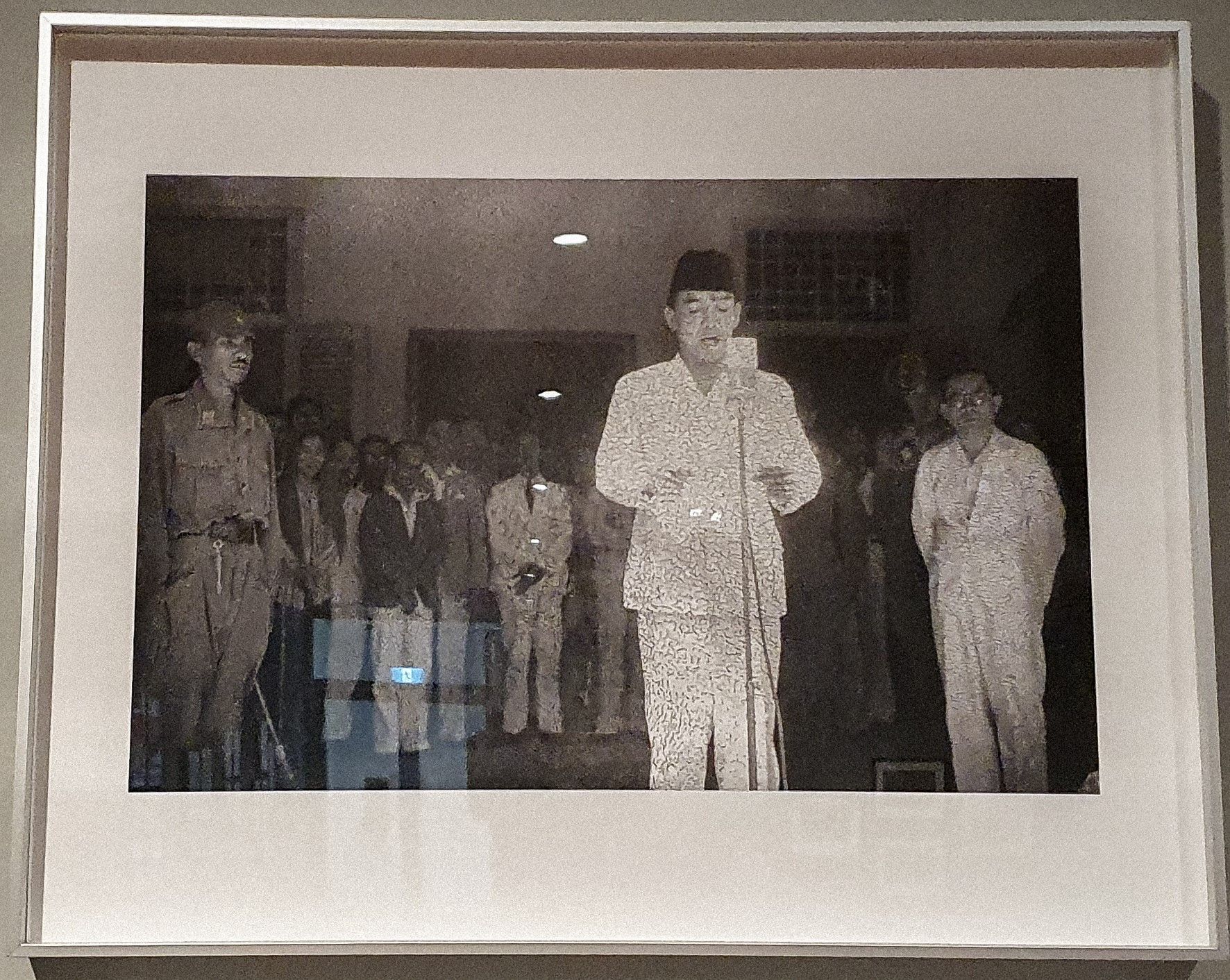

In spite of this, Living Pictures nonetheless excels at posing introspective questions, though not all of which are always answered. Still, this is done in a way that is more stimulating than it is frustrating. For example, one is likely to notice that a large part of the photographs displayed are in black and white. Although it is but a natural consequence of the once-nascent technology, one can’t help but contemplate what this achromaticity adds to (or takes away from) a photograph. Particularly, in political pieces like those from the Indonesian Press Photo Service (IPPHOS), the black and white palette adds much to the photograph by simplifying the scene.

As Soekarno, the first president of Indonesia, reads the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence at his residence in 1945, he is the only figure dressed in light colours. Behind him, his entourage remains discernible yet shadowed as the lower contrast between background values mutes details and expressions. There remains an almost spectral, holy glow around Soekarno’s figure, which is a result of both a spotlight as well as his light-coloured clothing. The reduction of the image to pure values heightens contrast, such that the highlighting of subject matter becomes possible.

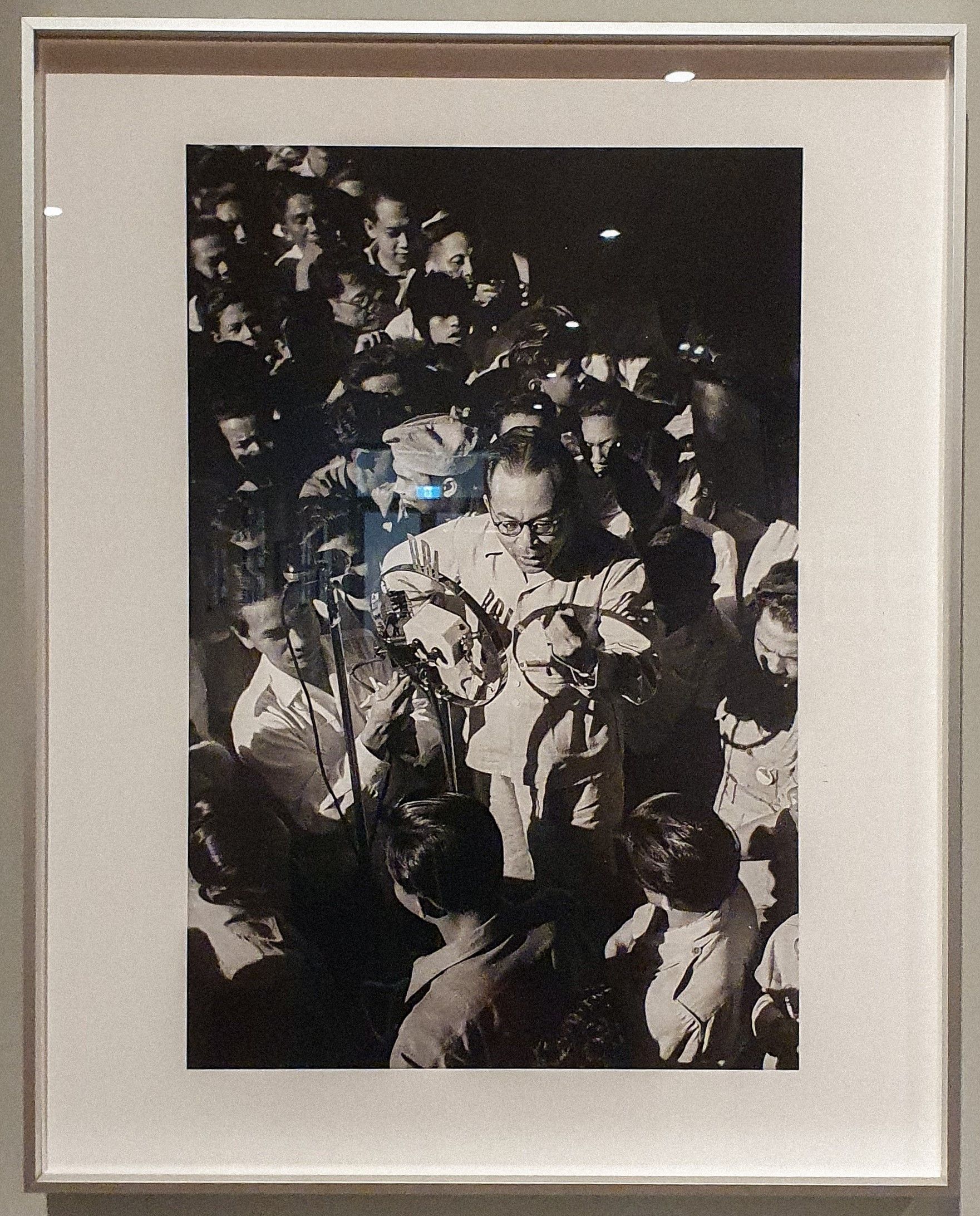

This effect can also be observed in a 1947 photograph of Indonesian Vice President Mohammed Hatta as he gives a speech at Manggarai Train Station. The photo is taken from a top-down angle, making visible the sheer number of supporters and guards present at the scene. Amongst this sea of people, the Vice President stands taller than everyone else—presumably standing atop an elevated plinth. Light streams in from the left, illuminating most of him while casting the crowd below in shadow. Once again, the political figure is highlighted and dramatised through strong contrast. One may argue that capturing a similar photo in colour would conversely distract from the individual meant to be in focus. There is also much to say about the metaphor concomitant with the colours white and black; purity and dull taintedness.

At the end of it all, Living Pictures tells a story of subjectivity.

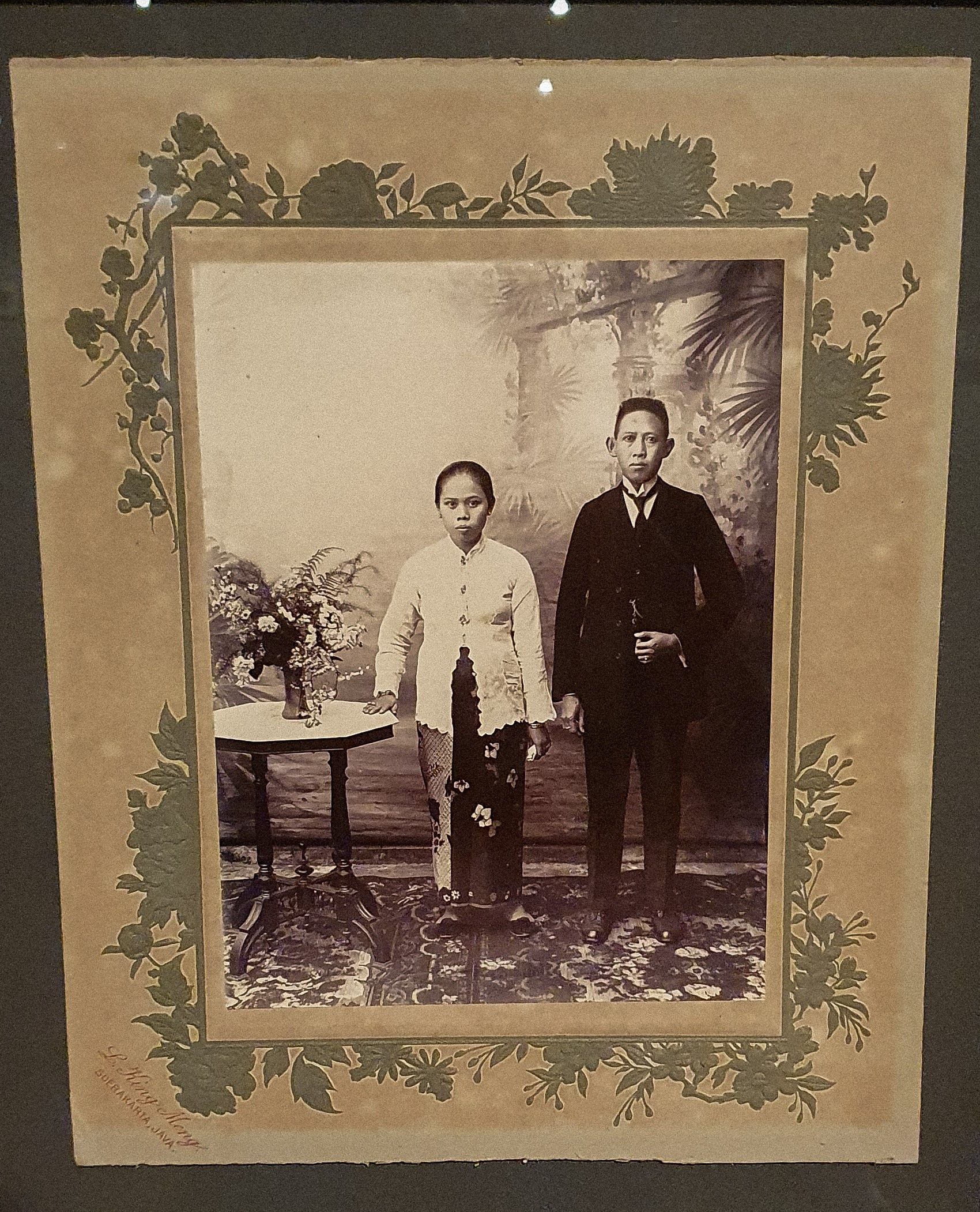

It is present in the specific ethnicities that colonisers packaged into postcards. It is present in the fabricated sets people posed (and continue to pose) in front of—ornate flower vases and luxurious rugs to backdrop the stiff awkwardness of inexperienced subjects. It is present in the collection of seemingly random objects, in all the digitally-remixed images and all their original, unedited sources. It is present in illustrated reference books, the newspaper and your grandmother’s ancestral tablet. Photography simply captures what one sees, and everyone sees differently.

Most importantly, Living Pictures shows us that some things never change.

We see that most photographs with children are at least a little blurred, and wonder if the exposure time had been unable to contain their youthful restlessness. We see portraits of individuals taken in studios—some appear serious and stiff as they stand amongst prop furniture and fabricated backgrounds. Others are photographed with the swagger of the modern-day influencer, their self-possession manifesting in commanding postures and subtle smirks. Both of such characters continue to surface in pictures taken today—just, perhaps, in slightly higher definition.

Technology may indeed be ever-changing. Other things, however—things like human creativity and our desire to leave a permanent mark on the world—never change. Living Pictures is the very testament of this.

Living Pictures will be exhibited at the Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery, Level 3, City Hall Wing until 20 August 2023. General Admission is free for all Singaporeans and Permanent Residents.