Natasha.

She was confusing, surprising, humbling. Although I may never come to understand her in her entirety, I’m glad we met.

The Singapore Biennale 2022—or Natasha, as its creators have so fondly named it—has been ongoing island-wide for around 5 months now. I’m slightly ashamed to say I haven’t taken the time to check out most of it. As the event now draws to a close, I still have only experienced but a small fraction: after it was announced that all closing week visits to the exhibitions at Tanjong Pagar Distripark would be free of charge, I finally, finally made my way there.

Close friends would’ve witnessed what I deemed Museum Day. I decided I would make it a self-care day of sorts, just me wandering around art exhibitions alone, in no rush and under no pressure. (In hindsight, even that wasn’t quite enough.) The galleries were spread out over the 1st and the 5th floors of the building—huge warehouse spaces with both large empty spaces and sectioned off rooms. I started off strong in the first floor gallery, which was pleasantly cool and dimmed.

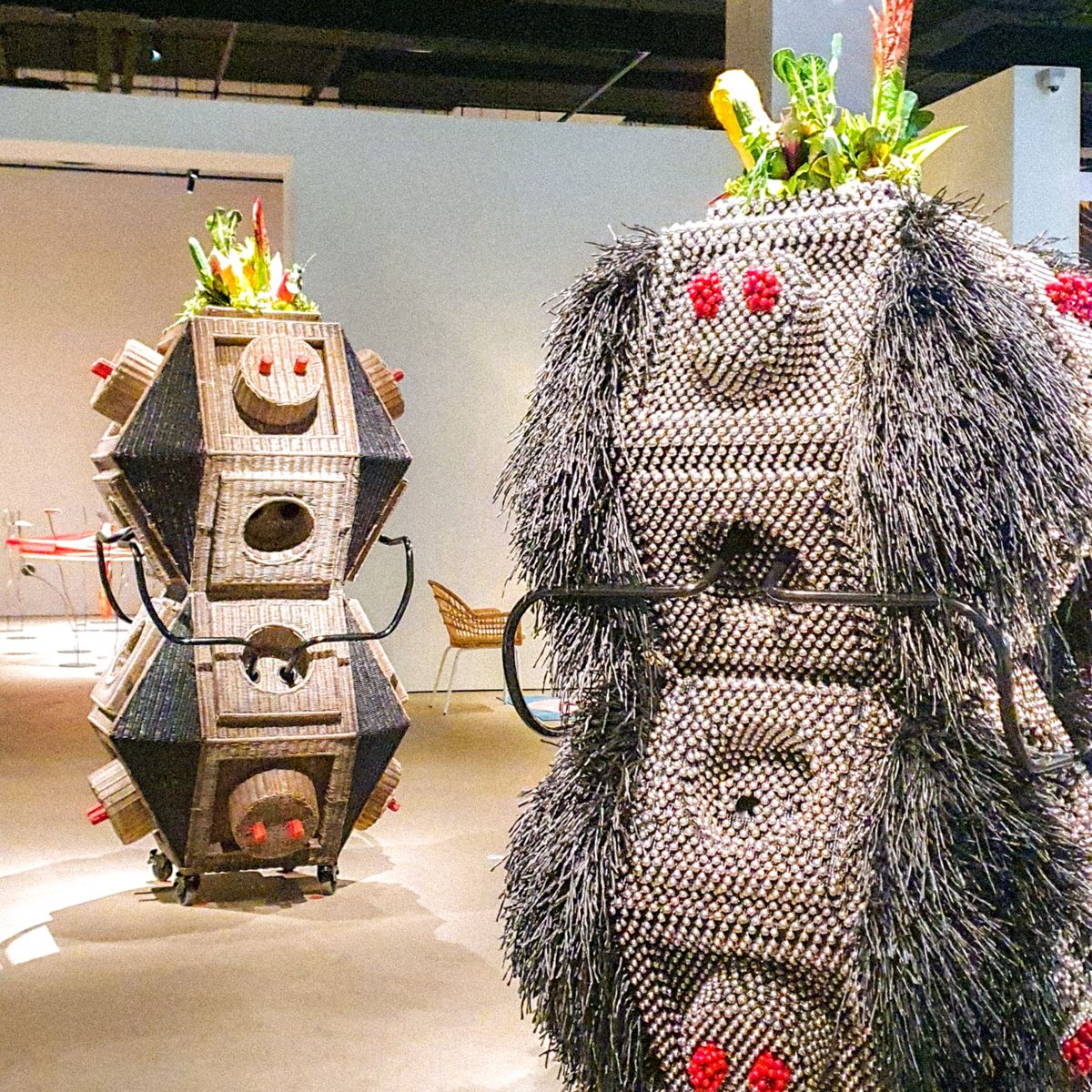

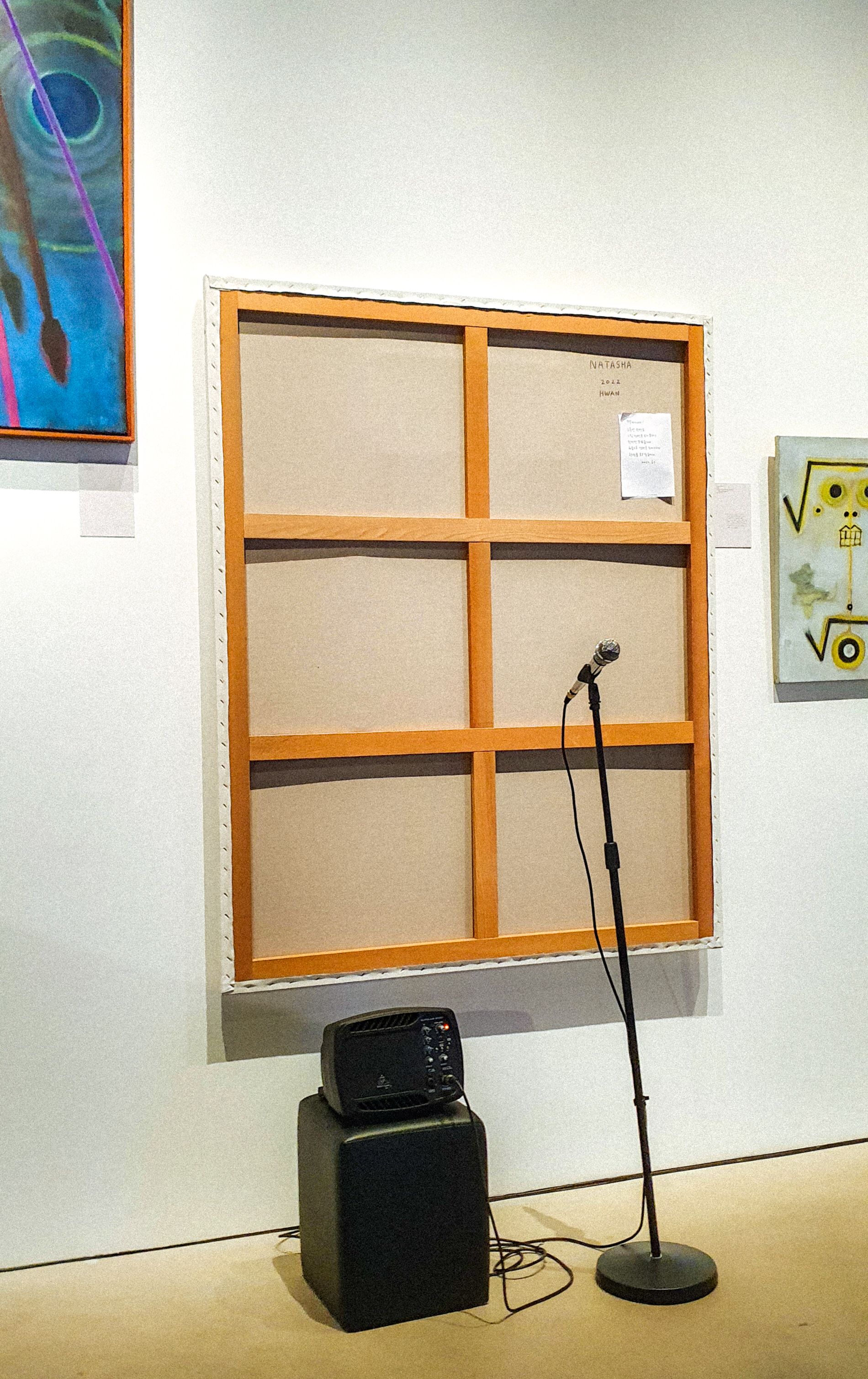

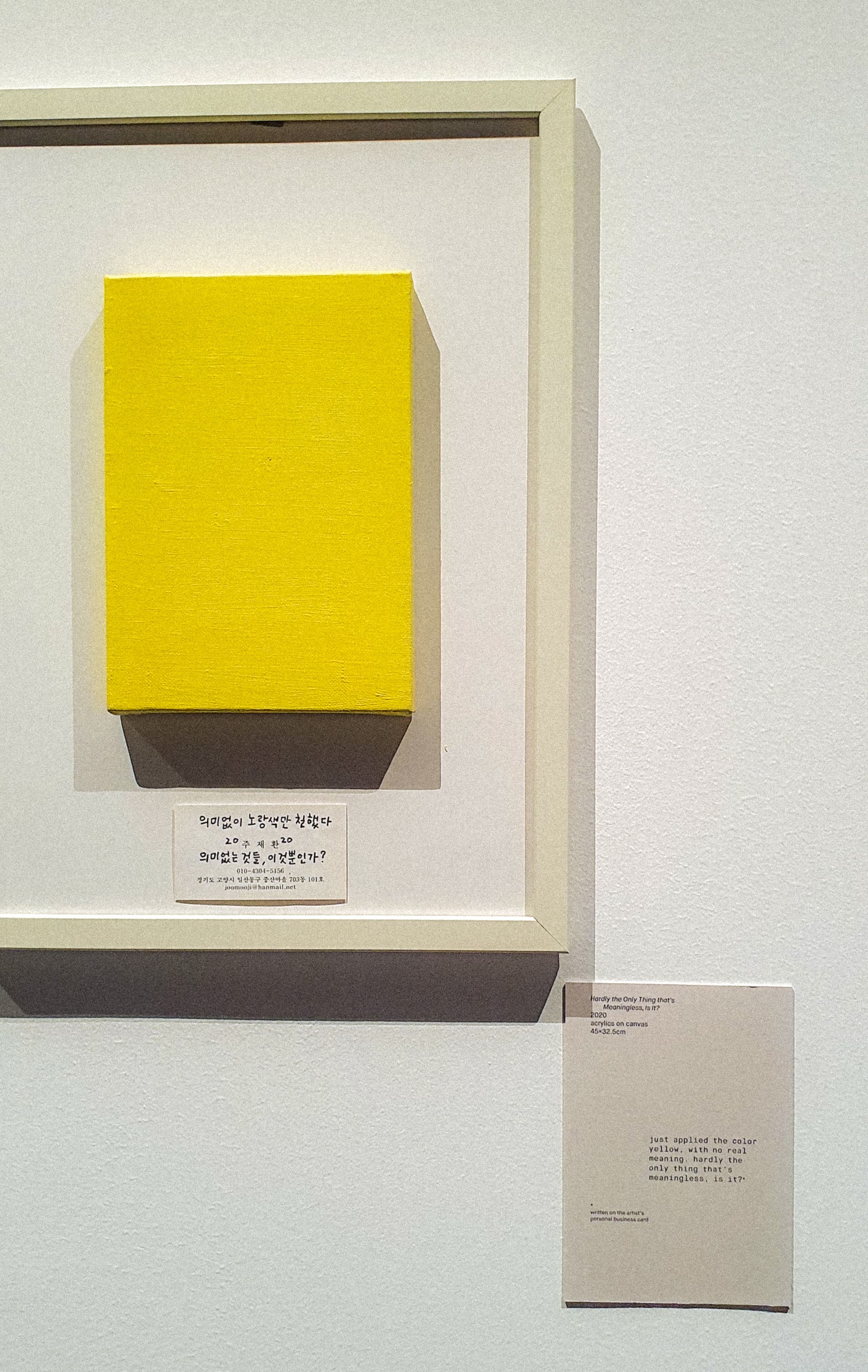

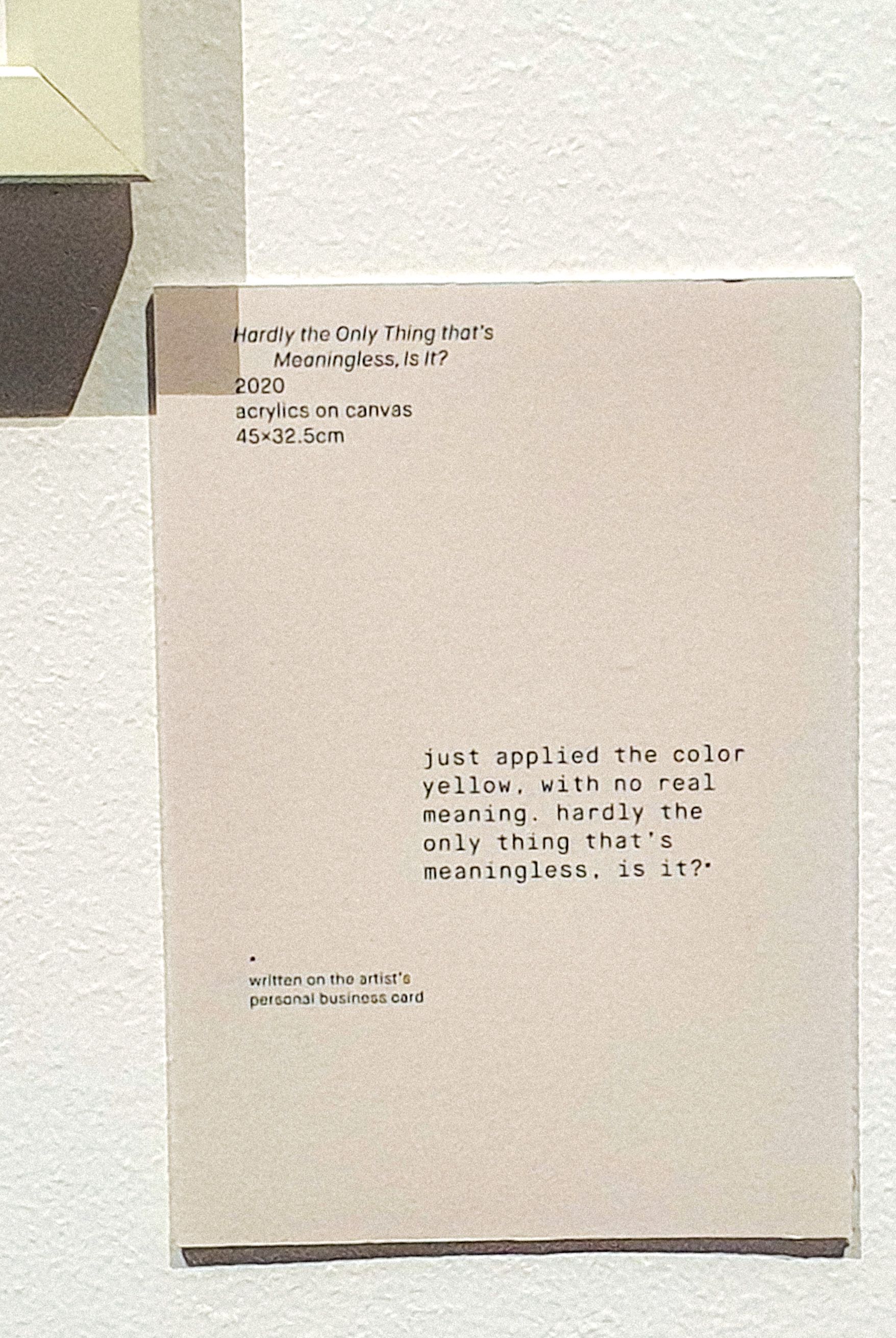

The first works I encountered were Joo Jae-Hwan’s bricolage paintings. They were the first canvases hung up right next to the front door, and I met them with a motivated yearning to understand.

Many of Joo’s paintings were not quite paintings—at least, not in the way one might traditionally imagine. Some don’t involve that much painting at all, and most were made using non-traditional art materials that were found in Joo’s studio, ranging from a dustpan to an empty egg carton.

Having Joo be one of the first few artists one is met with upon entering the gallery was an interesting choice. At first, I admittedly found myself slightly put off by the flippant simplicity of his works—certainly, most of them are far from the technically-demanding paintings or sculptures one might traditionally expect to find at an exhibition as reputable as this one. It almost seemed as if the artist were slapping anything and everything onto a canvas and calling it art. I believe this thought echoes in the mind of many when viewing contemporary art as well.

However, I came in determined to understand—and understand, I would. I stuck by the few paintings next to the door for a long time: if the organisers believed so strongly that Joo’s works were worthy of being included in an event like this, then perhaps there was simply something I wasn’t seeing.

I finally saw it, on the 5th floor of the gallery.

What exactly did I come to understand? It was this: Joo’s works are often visually, if not technically, simple. Made with common everyday objects that viewers are familiar with, it seems apparent that the artist likely does not consider artful or consummate presentations to be of greatest priority. In spite of this—or perhaps, because of this—Joo’s works are ingenious in the way they strike at the heart of issues, so irreverently and casually that one may often not even realise they have done so.

Not only were Joo’s bricolage paintings refreshingly clever in their artlessness, the artist’s sense of humour also clearly shone through in both the works themselves as well as the artist’s statements accompanying them. They were honestly delightful, and kept me going even if I didn’t quite manage to grasp every work in its entirety.

I came out of the exhibition bearing a strong sense of admiration for Joo Jae-Hwan, knowing I would hardly be able to conjure the same witty punchlines he did on my own (especially given the sheer diversity of both his materials and the societal topics he discusses).

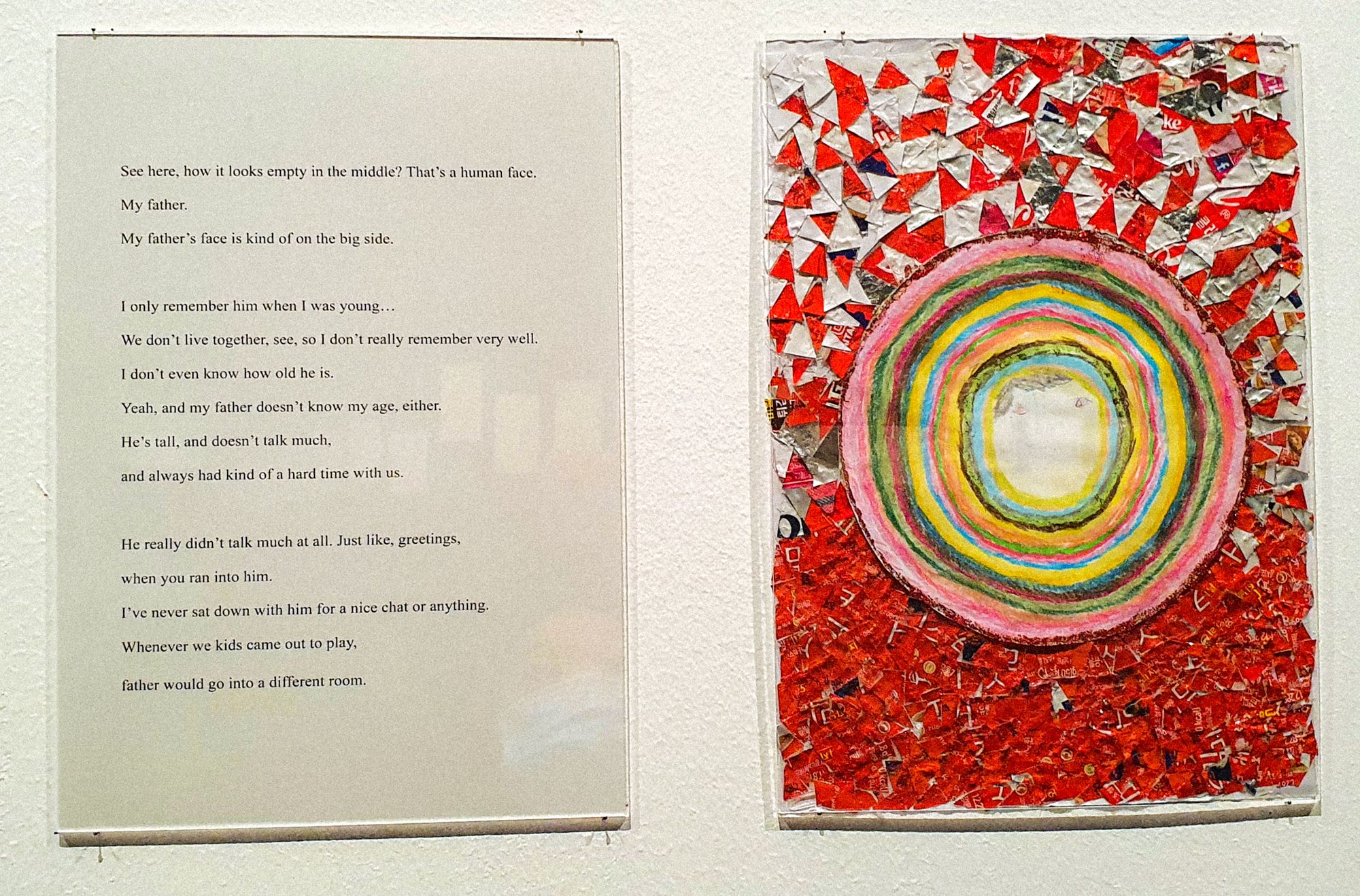

It was much later in the exhibition that I chanced upon Yoon Mi Ae’s Communion Wafers (2017-2022), on the stuffy 5th floor. To be honest, they hadn’t particularly stood out to me in the beginning—in fact, I’d wandered past a section of the wall onto which her glittery, kaleidoscopic circles were hung before even noticing they were there. I’d stopped for a second, moving closer to view the uneven, hand-cut triangles of gum wrappers and instant coffee packages—then moved on.

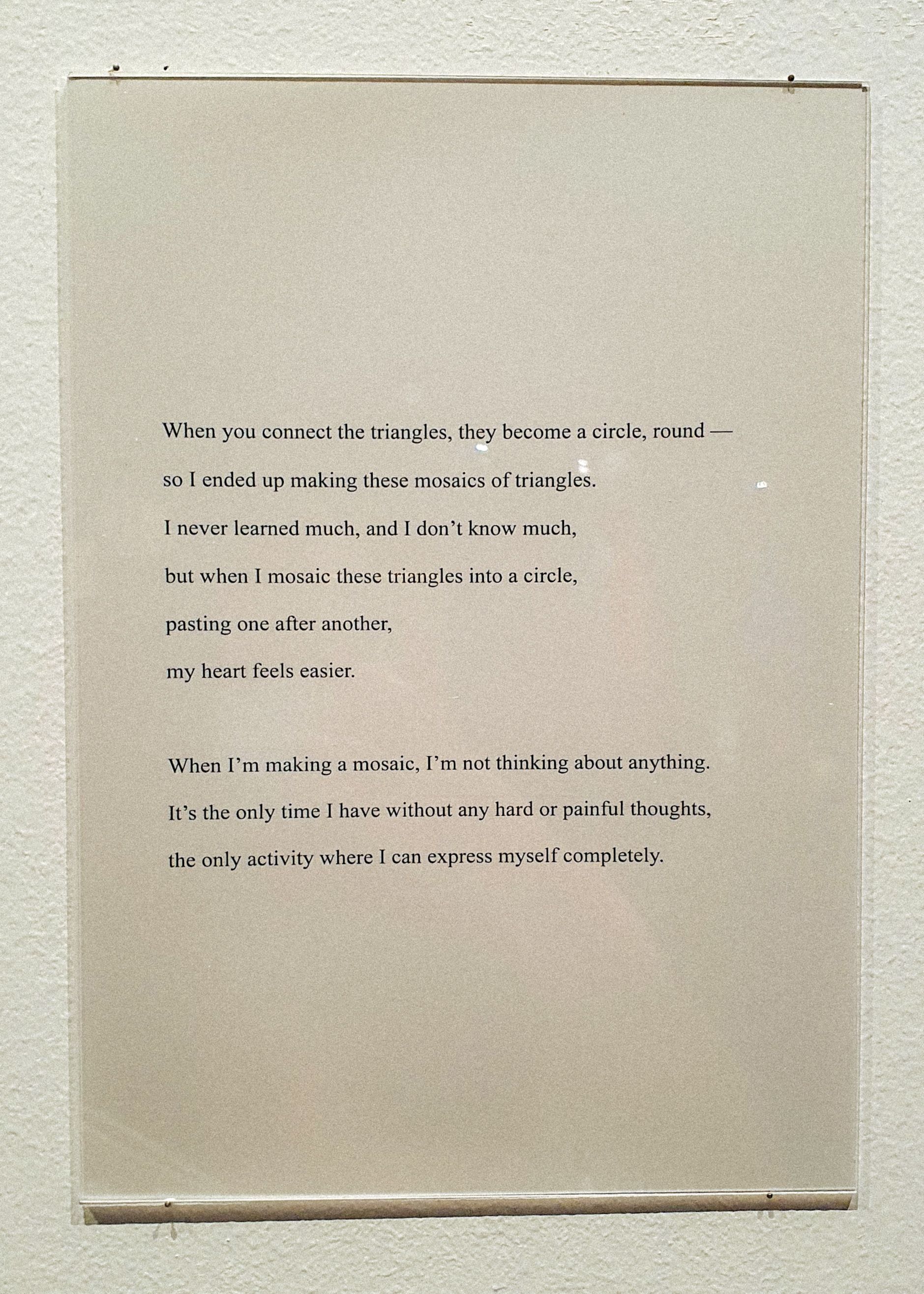

At that point, I was truthfully rather tired. There was not one corner of the room that didn’t feel dense and uncomfortably warm. The lights, dimmed for atmosphere’s sake, only added to the disorienting, reverberating echoes from nearby video installations. I was also growing frustrated at my failed attempts to understand most of what I was seeing—which of course, only made it even harder to patiently process any subsequent work. So, Yoon’s sparkly circles didn’t stand out to me. I’m slightly ashamed to say that the forbidden thought had even crossed my mind: ‘Why is this here? I could’ve done this as a 5 year-old.’

I looped around the standalone wall, to its other side. It was there that I finally slowed down and tried to recalibrate. What I found was a multicoloured spiral set against a backdrop of red and white triangles. In the middle of the circle was a man’s face—although drawn rather crudely, the presence of a recognisable subject made me stop to read its accompanying write-up.

The artist’s musings were clearly tinged with sadness, yet I found a childlike wonder in this piece. Indeed, the man’s face appeared ghostly and almost faded in the centre of the circle—whether or not this was intentional, I think it provided an apt image of how little the artist knew about her father. What remains is a childlike depiction of him, surrounded by circles coloured in both dark and light colours as if to represent mixed emotions. Majority of the lighter colours are found on the inner layers of the circle: yellows, oranges and light blues, closer to the man’s face. As a result, a soft glow almost appears to radiate from the centre of the ring, surrounding the father’s face in a halo.

The background also provides much visual interest to this piece. As Yoon used product wrappers to construct the overlapping triangles, their original print can still be seen. This results in a sprinkling of korean (and sometimes english) characters throughout the background—yet, having been cut up and stuck together closely, none of the characters can form coherent words. They fill up the page in a complex, haywired manner, yet give us little to work with. One gets the impression that there is much to be said by the artist about her father—clearly, there is much that is felt—but perhaps even Yoon herself hasn’t quite made sense of this tangle of thoughts and emotions.

The bold red triangles rise, then gradually disperse. Intrigued by the simple yet heartfelt passage, I started reading the rest.

It finally started to make sense to me, at this point. Before this, I’d been sceptical. Like most amateur art viewers, I’d wondered what was so special about these multicoloured spirals when they appeared to be something a young child could’ve made at kindergarten. But reading these musings that came from the artist herself, I understood.

I can’t tell you exactly what I understood, though. All I can say is that suddenly, all of it made sense to me, both faces of that wall punctuated by Yoon’s works. I understood why someone felt they ought to be there. Perhaps it was that admission of struggle, of pain and distress—something we all know so acutely as human beings. I was struggling, and this was the only thing that made it feel better. Not once had Yoon’s communion wafers pretended to be something they weren’t. To me, that was enough to make me understand the value of these glittery spirals. In that stuffy, 5th floor warehouse space, I found something important.

In retrospect, I’m glad I gave the galleries a visit. Admittedly, the day hadn’t gone perfectly—I hadn’t understood every single work I’d seen, maybe not even most. I’d gotten frustrated, tired; at some point I itched to leave. Yet, I suppose it’s hard to get to know someone fully after a single visit. Her curators had named her Natasha for a reason, and if it was anyone’s fault that I found myself short of time to make sense of all her complexities, it was mine. She was confusing, surprising, humbling. Although I may never come to understand her in her entirety, I’m glad we met.

Find out more about the aforementioned artists here:

Joo Jae-Hwan

https://www.singaporebiennale.org/artists/joo-jae-hwan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2mrW7kPhzp4

Yoon Mi Ae:

https://www.singaporebiennale.org/artists/brightworkroom

Brightworkroom (est. 2008) is an artists’ group based in Seoul and founded by novelist Kim Hyona and visual artist Kim Inkyung. The group engages and works with neurodivergent artists and experiments with creative and communicative methods through diverse art forms.

For the Biennale, they present the works of three women artists, namely Kym Jin Hong, Na Jeong Suk and Yoon Mi Ae.

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2022/09/690_311820.html?utm_source=KK