What Does Sound Look Like?

Take a closer look, and you may just hear the cicada’s relentless song.

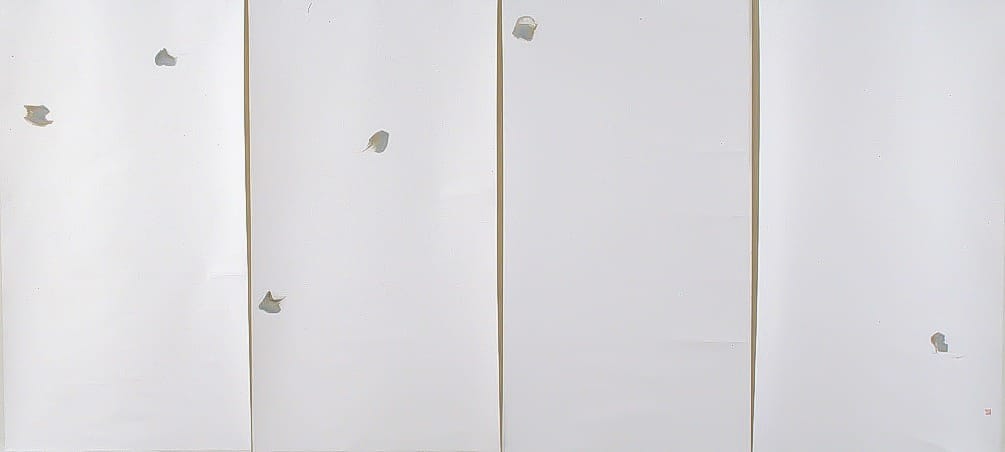

Chua Ek Kay knows. His 1995 painting, Song of Cicada, is a portrait of exactly that: sound. Nonetheless, like with most good art, this does not stop viewers from finding something else within—leaves swirling in the wind, footprints of a woodland creature, or even cicadas themselves.

Chua Ek Kay (1947-2008) was born in Guangdong, China. His family migrated to Singapore three years later, and here he would remain for the rest of his life. Owing to both his racial heritage and family’s way of life, Chua found himself surrounded by Chinese cultural influences growing up. He excelled in Chinese calligraphy as a child and, in his late twenties, came under the tutelage of Singaporean master ink painter Fan Chang Tien. Yet, he only became a full-time painter at the age of 38.

Despite his early foundations in Chinese calligraphy and ink painting, Chua’s later artistic explorations saw him moving away from traditional Chinese techniques to study Western art in both Singapore and Australia. These dual cultural influences irrevocably shaped his artistic practice, earning him the title of “the bridge between Asian and Western art".

Song of Cicada (1995) is paradigmatic of this cultural fusion. Painted with Chinese ink and pigments on large sheets of rice paper, this tetraptych confronts viewers with its expansive planes of white. Grey ink markings are scattered unevenly across each identical sheet, none appearing uniform in shape. Each droplet bears little detail besides its internal colour gradient and organic form.

The apparent lack of other subject matter in the painting centres our focus on these droplets immediately. Despite appearing small and dull-coloured, the grey daubs showcase Chua’s ability to create dynamism through the slightest of gestures—a flick of a brush here, a gentle rounding off of a shape there. His early training in the 写意 (xieyi) style shines through in these expressive brushstrokes that evocate the inner spirit of subject matter, transforming these grey markings into lively creatures that flutter and swoop in an invisible wind.

The fragmentation of the work into 4 identical panels further adds to this sense of movement. It may first raise questions: is the painting representative of a singular scene, broken up visually? Or is time instead fragmented, the pieces of rice paper displaying four separate moments? Perhaps the painting does not intend to mimic a visual scene at all. Mirroring the reading of sheet music, the regular segmentation of the work tends to lead our eyes from one end to another. Chua’s grey daubs read like musical notes, their placement—whether purposeful or random—creating an undulating visual that rises and falls, interrupted only by the break in their physical backdrop. The regularity of these breaks confers a sense of rhythmic progression to the piece, evoking the steady rhythm of a cicada’s song without disrupting the loose organicity of Chua’s grey forms.

Only male cicadas sing. During the warmest periods of the year, cicada nymphs emerge from the ground, moulting into winged adults and assuming their places in the summer’s choir. Yet in Song of Cicada, there is seemingly little allusion to summertime. Artworks that are largely considered to encapsulate the essence of summer, from Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) to Sorolla’s Women Walking on the Beach (1909), all have several elements in common. Sunlight drapes across the land in large, golden sheets, and colours are usually warm. Contrast is often emphasised between lit and shadowed areas. Such works often attempt to match the blazing intensity of summertime through their own visual intensity.

No such thing takes place in Song of Cicada. Colours are low-contrast and barely even warm. As a result, the painting appears anything but intense. This limited visual interest plays an unexpected role: it transforms the empty background into a character of its own. The pristine paleness of the rice paper evokes a sense of serenity, yet its slight texture—owing to its fibrous material—likens it to visual white noise that we instinctively overlook. Only when we actively re-approach the painting may we pause to consider this emptiness as an independent subject matter.

This principle is one long-entrenched in traditional Chinese painting, known as 留白 (liu bai)—literally translated, "to leave white [spaces]". Set against a blank or ambiguous background, subject matter is often situated out of context and conversely defined with clarity. This stark juxtaposition of empty voids and filled spaces reflects Taoist ideals of universal balance, and is also what transports us to a warm summer’s day: the cicada interrupts the noticeable stillness of summertime with his equally-conspicuous song.

Song of Cicada is a portrait of sound, masterfully borne of both East and West. We see Eastern foundations in its materials, its delicate artistry and its reverent observation of nature. In equal part we find Western influences in its openness to imagination and abstraction. Like with most good art, viewers may see various likenesses or none at all. Take a closer look, however, and you may just hear the cicada’s relentless song.