Why is Modern Art so Expensive?

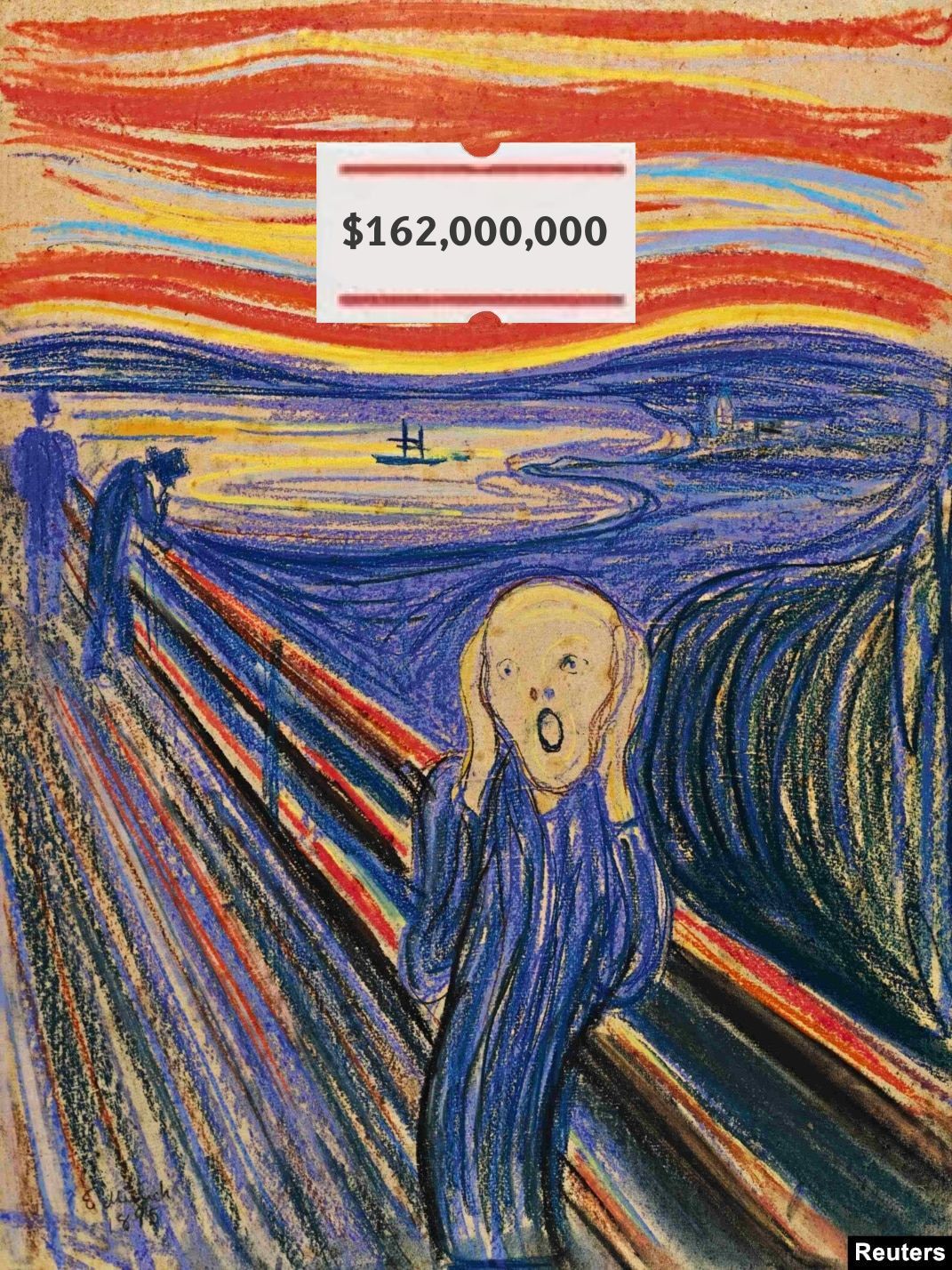

Artworks are simply sold for what people are willing to pay — and it’s safe to say that people are willing to pay a lot.

I watched this video a few days ago and, like several comments frustratedly pointed out, it barely gave a substantial answer to the question posed: Why is Modern Art so expensive? I then decided to take a scroll through the comments, but quickly began to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of hate people were giving to modern art—both artists and non-artists alike. Admittedly, I can easily see their point. Artists practising more technical art forms feel sidelined by the popularisation of this new artistic style that, on the surface, appears much less demanding in terms of skill.

On the other hand, the common person may often feel as if the fine art market operates on a plane that is completely different from that on which regular society operates. Of course it remains a mystery to many—in what world would a banana taped to a blank wall cost anything more than, well, a banana? Where exactly is its extravagant perceived value derived?

Personally, I believe myself to be slightly more open-minded than the average person. If that many people are clamouring to view and buy these works of art for exorbitant prices I don’t understand, then perhaps they simply possess a value that I’m not yet privy to. Perhaps I’m just not knowledgeable enough about the subject to comment on it yet. Rich people will always have their secrets, or whatnot.

My imposter syndrome is a topic for another day, though. I thought it was especially apt to build the first article around this topic of price and value because many people in Singapore hold similarly critical opinions about it. I think this, in fact, is intensified due to our culture of pragmatism—trying to argue for the unseen value in a seemingly lofty art piece is probably just going to get you scoffed at.

By definition, modern art includes artworks created between the 1860s to the 1970s that mainly aimed to discard tradition in favour of experimentation. This broad category encompasses painters like Vincent van Gogh and Picasso, as well as other artists whose oeuvres escape straightforward definition, such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. To the layman, however, the ‘modern art’ in question is often loosely interchangeable with the terms ‘abstract art’ and ‘contemporary art’. These forms of art are often associated with lower skill and effort, yet often have unfairly exorbitant prices.

Why, then, is modern art so expensive? And why do so many believe it shouldn’t be?

One comparison I often enjoy drawing is that between modern art and classical music. While classical music certainly isn't for everyone, it is reasonable to observe that most people still accord famous classical pieces with their due respect and recognition, whether or not it is their cup of tea. This is in spite of the fact that realistically, classical music is just sound—just like how Mark Rothko’s colour field paintings are just colour. What exactly does Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 tell us that Jackson Pollock’s unfettered paint splatters cannot? Does it then, perhaps, all boil down to the amount of perceived effort put into making each piece?

It is understandable that effort is often such an important benchmark for determining value. Humans are, in our most basic essence, tribal creatures. In any community, one’s value is most commonly tied to what one can contribute to better the lives of everyone else. In this sense, a musician who has taken years to hone his craft would certainly appear to hold greater value than an artist who can paint canvases with two-dimensional blocks of colour.

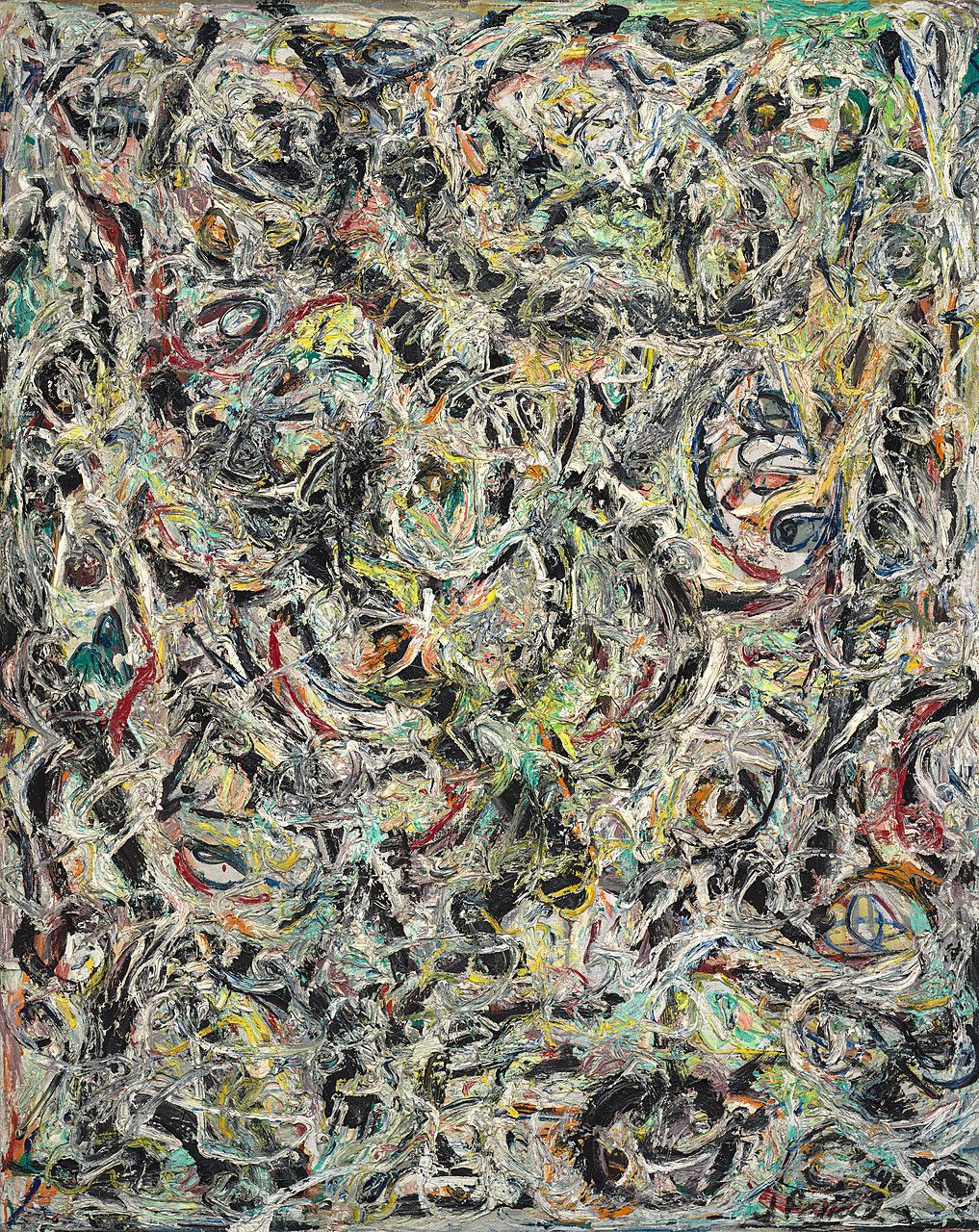

However, in terms of artistic practice, is effort really a one-time phenomenon or something that can be measured over time? Let's take Jackson Pollock for example, an American painter who was best known for his novel 'drip technique' of pouring liquid household paint onto a horizontal canvas to create chaotic suspensions of tangled lines.

Sure, anyone can make a Pollock drip painting—after all, all he seemingly did was splatter paint across a canvas in random directions, right? Yet, there are two things to note here: firstly, yes, you could’ve done that too—but you didn’t. Pollock’s work as an artist exploded into fame precisely because he started making art in a way others weren’t, or hadn’t cared to. He brought something new (albeit controversial) to the table, and this was instrumental in changing the course of art history. His drip paintings will carry this legacy forever. Naturally, this accords them with value.

(It is also important to note that many artworks start fetching exorbitant prices only after the artist is dead. As no more original pieces can be produced, this understandably makes the existing works all the more exclusive and hence valuable.)

Secondly, Pollock hadn’t simply woken up one day and decided to start dripping paint onto his canvases. In fact, he’d only achieved the iconic style of his drip paintings late into his career—before that, he had actually started out creating surreal works that were, in fact, very much figurative.

He’d then progressed to applying paint directly from the tube, creating paintings with thick, richly textural surfaces. This element of texture would be preserved as he finally discovered a niche in drip painting.

Hence, the value that is imbued in a singular Pollock painting need not merely be derived from the effort taken to create it, but can also be derived from the many years of experimentation necessary to arrive at this final product. One is not merely paying for a bunch of paint splattered onto a canvas, but is also paying as recognition of the artist’s time, energy and dedication towards developing his craft—of which the artwork is physical proof.

This, of course, is only one of the many possible perspectives one may take with regards to this topic. The reasons mentioned above may apply to some artworks, but not others—in most cases, the price of an artwork is influenced by a multitude of factors and remains highly subjective.

There is also a stark difference between the pricing of artworks in the high art market, in comparison to the rest of the art industry: the high art market is often moreso about profit than it is about art itself. Below is another compelling video that validates much of the cynical mockery that the fine art world receives.

In conclusion, a piece of modern art can be sold for millions because of its historical context and importance. Yet, its buyer could also be purchasing it as a means to hoard wealth. These two reasons are far from mutually exclusive. The most expensive of modern artworks may be compared to luxury items like bags or cars: they’re priced high because they’re representative of a widely-acclaimed brand. Could the rich be purchasing them merely as a means of investment or to flaunt their wealth? Yes. Could they nonetheless be of high quality and a result of decades of meticulous development? Also yes.

Objectively, then, is modern art overpriced? Probably. But in the context of fine art, prices don’t come about objectively. Artworks are simply sold for what people are willing to pay—and it’s safe to say that people are willing to pay a lot.